The truth lying behind a ‘Hello World!’ executable

Whenever we are learning how to program in a compiled programming language, reading a book, we are told by it to try making an ordinary program that does nothing but prints into console a ‘Hello World!’ message. After we have made, compiled, and run it, the book boastfully says that we now have made the program.

What?! Is it supposed to mean that I have become a programmer as long as I have made the program? Since only programmers can make programs, but meanwhile, running a ‘hello world!’ for the 100th time, you realize that this is only beginning of the book and you have not read even a half, and the question arises, ‘Should I continue reading the book, or maybe am I done, ready for making programs?’

The vast majority of the ‘Hello World!’ programs exemplify nothing. Whereas for a scripting language such an example might be convenient, it is inconvenient at all for a compiled language, because a system developer should know not only a language structure, its operators, etc., but also one should be familiar with linking and loading processes happening under the hood, to see, for example, what exactly a ‘main’ function means, what exactly it is, why this name ‘main’ might not be changed, and why it even must be.

Let us consider the following ‘Hello World!’ program written in C programming language (Example #1):

#include<stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

char *hw_string = "Hello world!";

printf("%s\n", hw_string);

return 0;

}This example shows us how to print the string to a terminal. But why should we choose C or C++, or even what have these languages ever been made for, since Assembler have allowed us to do the same operations on data long before the invention of C or C++? What for we should be grateful to those high-level languages?

Let us continue. Should the aforementioned source code (Example #1) be thrown directly into a processor? Can a processor execute this code as is? We ourselves can try to check it.

I copied the source code of Example #1 into hw.sh, added executable permission via chmod a+x hw.sh, and run it through terminal directly typing ./hw.sh [+Enter]. The following I got as the result:

./hw.sh: line 3: syntax error near unexpected token `('

./hw.sh: line 3: `int main(int argc, char** argv)'Hmm, this looks that a shell treated hw.sh as though it were a shell script file. But we want this file to be pushed directly to the processor! To do so, we need a new program that can get anything given and arrange execution of no matter what in its hands. This can be done by the following program called ‘execve’:

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <errno.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

printf("Program to be executed: %s\n", argv[1]);

execve(argv[1], argv + 1, NULL);

printf("errno=%i, error text: %s\n", errno, strerror(errno));

return 0;

}Execve enables us to give it anything we want, and then it passes this to the sys_execve linux kernel system call (https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v2.6.35/source/arch/alpha/kernel/entry.S#L925, http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/execve.2.html). By doing that, we could see what happens if we pass the aforementioned C source code of Example #1 to it. I did it, and the following was an output:

Program to be executed: hw.txt

errno=8, error text: Exec format errorAccording to https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/include/uapi/asm-generic/errno-base.h#L12 , this error comes right from the kernel, and it means that I tried to load a file of an inconvenient format, and it rightfully failed. It is true, a processor of x86 family can run the program of a specified format. We cannot pass into it any C source code and wait for it to be executed properly. To date, Assembler is the only language that can be recognized by a x86 processor.

This means that we somehow need to translate our C source code into Assembler recognized by a processor. It can be done via GCC (constituent of GNU Compiler Collection https://www.gnu.org/software/gcc/) by putting the source code into file with the ‘.c’ extension (for example hw.c) and executing the following command:

$ gcc -O0 hw.c -o hwcNow we can find the file ‘hwc’ in the current directory and try to run it:

$ ./execve hwc

Program to be executed: hwc

Hello world!Yes we did it! We can see now that processor, which, this time, was given the file of a convenient format, executed it and we can happily observe an expected result.

But what now does the file recognized by a processor look like?

In doing that, Ghidra (https://ghidra-sre.org/) will help us. Let us look inside the ‘hwc’ executable.

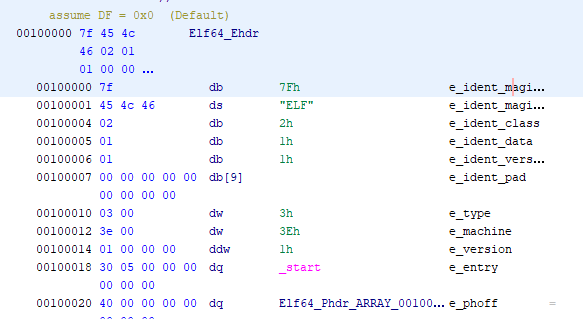

At the very start of the hwc file we can see that it starts with the number 7Fh and letters ‘ELF’. This is called magic numbers, and in our case the final magic numbers look like string ‘ELF’. And it is true, those words are intended to be ELF since them stand for Executable and Linkable Format (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Executable_and_Linkable_Format). Why those numbers are called magic is simple. Magic numbers help operating system distinguish between a vast variety of file formats. The distinguishing process help a processor, on early stages, ensure that file is given in a suitable format in an ongoing circumstance.

There are more numbers before a program itself, and all those numbers are called a header. A header of an executable program consists of tunes as to how much memory a program requires, at which memory address it should be placed, and many other. The numbers of our interest now are at the line where word ‘_start’ highlighted in red. This part of a header is called Entry Point, and it points to place in file where the actual program begins. (As a matter of fact, there are executable programs without any headers, at all, only code is in those files at the very beginning, and this format (pretty popular in previous years) is called ‘.com’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COM_file)

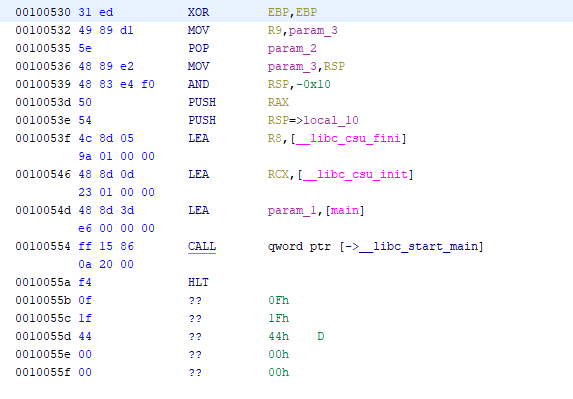

If we double click on it, we fall into the following section of the hwc:

Now you can look on what does Assembler language look like. You can recall the function ‘main’ in the above source code which now passed into the function ‘__libc_start_main’ as parameter. This is a convenient way for all executable programs that are compiled with GCC to start through this function.

After calling __libc_start_main you can see HLT instruction and unrecognized bytes. This is okay since by standard function __libc_start_main never returns a thing, and if it were return something somehow, a processor meets HLT instruction which in such circumstances would raise an exception and OS terminate the executable. An exception rises because HLT instruction have such privileges that it only can be executed only by OS kernel or some OS drivers.

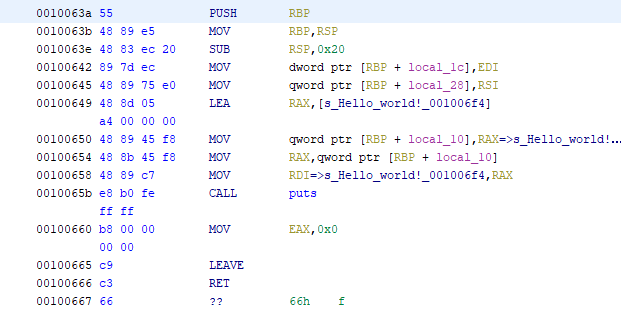

If we double click on the function ‘main’ we fall deeper:

Here we can find calling function ‘puts’ and then leaving from the main with exit code 0 (MOV EAX,0x0).

That is all. Think about it, that if we were to write our program in Assembler, we should take into account a variety of circumstances and standards. Writing a program in C programming language, we are released from that duty and can focus only on accomplishing task without thinking of properly organizing memory, recalling a name of system call to, for example, write a string to a console or open a file.

But if we were to write the same program in Assembler, it might look like that (NASM):

global _start

section .text

_start:

mov rax, 1

mov rdi, 1

mov rsi, msg

mov rdx, msglen

syscall

mov rax, 60

mov rdi, 0

syscall

section .rodata

msg: db "Hello, world!", 10

msglen: equ $ - msgAnd that is all. Consider the difference. This program is more concise than the code that was generated by GCC, but you have to do many things by yourself, for example even copying an array or prepare a number to be printed on screen because processor have no such a function that could transform number into string.

There is one more interesting thing. The size of file that is generated from Assembler code:

$ nasm -f elf64 -o hw.o hw.nasm && ld -s -o hwasm hw.o && rm -f hw.o

$ ls -la hwasm

-rwxrwxrwx 1 sergei sergei 464 Apr 15 23:28 hwasmThe size is just 464 bytes, and it is statically linked. Static linking means that no library is necessary to be somewhere for this executable to run. If we statically compile C language, the results will be significantly different:

$ gcc -static -O0 hw.c -o hwc

$ ls -la hwc

-rwxrwxrwx 1 sergei sergei 844696 Apr 15 23:32 hwcHere, the size is 844696 bytes for the same statically linked program by in C programming language.

GCC bears all its burden of functions that might be used in program. It does not analyse deeply as to which function might be used or not. By looking at Assembler written by human and generated by GCC compiler, you also can consider that generated code does significantly more things than human code does. And this is the price we are paying when we want to focus only on algorithms without bothering ourselves with stuff happening under the OS hood.

This is for what we are learning higher-level languages or scripting languages like phyton, javascript, and so on. They significantly facilitate to do our task, job, leaving us to focus only on our ideas, on our algorithms.

But of course, there are might be some circumstances where we should take Assembler and jot down a program ourselves, since we want be ensured as to what instructions exactly will be executed by a processor. Doing this, we are now focused on algorithm optimizations, and in that area (optimizations of algorithms) it is hard to find generator that gives a code that could not be improved.

This is what ‘Hello World!’ looks like.