Haskell Injectivity Of Type Families And Reasons Of Its Ambiguity

Recently, I encountered an ambiguity while had been using type families, and I found that there almost nothing was written about it regarding the reasons as to why one should use injectivity and why GHC sometimes struggle to infer a type, consuming type families and its application way.

This article is a compilation of numerous information sources that I have found and a try of contribution towards filling this gap in the subject matter.

What exactly the Type Families are? According to documentation, they are “a Haskell extension supporting ad-hoc overloading of data types.” They can be considered as a function on types. That is, you pass to the function some type and it returns you another.

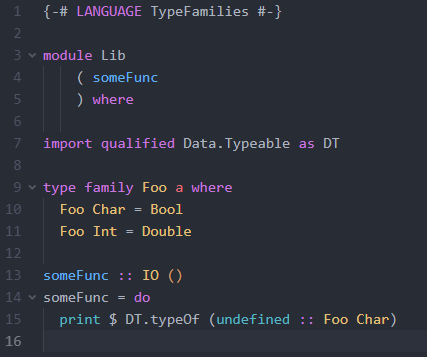

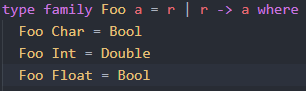

Let us start with the following example:

The output of this example is “Bool.”

In the example above, we have declared type function Foo and that if we pass Char to Foo, it should return Bool, but if we pass Int, it should return Double.

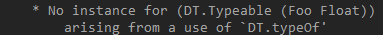

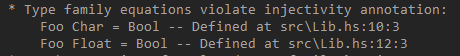

What if we pass a type that was not defined in the Foo, type family? For example, we can pass Float. GHC would say the following:

That is, GHC indicated that the Float type was not defined in the Foo type family, meaning that the Foo did not know what to do with the Float as to what a type exactly it should return back.

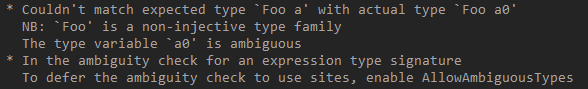

What will happen if we pass a type variable instead of any type? For example, we can change the print line to the following:

Now, not only did GHC say that Foo knew nothing about a type that was passed to, but GHC also told that we were passing type that was unknown at all. Therefore, GHC and Foo did not know what the type was, but that time GHC did say something about injectivity – “`Foo’ is a non-injective type family.”

According to Chapter 4.2.4 “Matchability” of the great and famous dissertation “DEPENDENT TYPES IN HASKELL: THEORY AND PRACTICE” by Richard A. Eisenberg et al., it means the following:

Definition (Injectivity). If f is injective, then f a ∼ f b implies a ∼ b.

In our case, it should be as “Foo a ∼ Foo b.” At first glance, we should not encounter any problems with that. Let us try:

Foo Char(a) ∼ Foo Char(b), consequently Bool ∼ Bool, and Char ∼ Char.

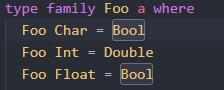

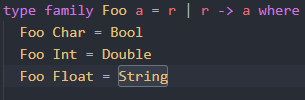

There is nothing like a problem, and our Foo looks to be injective. Then, let us add the new definition in Foo so as Foo will be the following:

Taking the changes that were mentioned above into account, let us try next:

Foo Char ~ Foo Float, consequently Bool ~ Bool, but Char does not equal Float.

That is the problem. “Ok, but why should I bother about injectivity?” you may ask.

The following are cases of using the type families that can be found to be a problem if type families are not injective.

First case

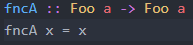

Let us add the following function to our source:

And also we will change our print line to the following:

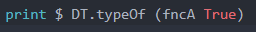

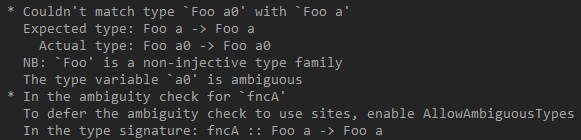

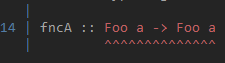

GHC said the following:

It seems that GHC did not even try to infer the type and finished compilation right on the definition of fncA:

Why?

Let us pretend that we are GHC. Thus, seeing that type Bool was passed into fncA, we should infer the type “a” of “Foo a.” Concisely, we should pattern-match “Foo a = Bool.” Hence, we should look at the definition of Foo and find the line that returns type Bool. Surprisingly, there are two such lines:

Foo Char = Bool

Foo Float = BoolThat is the reason why GHC finished with the error message. There no ways to say whether “a” should equal Char or Float, and of course “a” can be equals to both simultaneously. Now, we can say that Foo is not injective, and being non-injective prevents a type inference. In fact, GHC would not do these checks; it just sees that we use non-injective type family and returns error by implication that there could be entries in Foo type family that could return the same types.

Fortunately, there is a way to indicate that a type family is injective. The TypeFamilyDependencies extension enables us to do it. After we have enabled this extension, we should change the Foo type family declaration to the following:

It looks like the Functional dependencies. But still GHC returns the following error:

GHC is absolutely right. Look at the declaration of the Foo. It means that result ‘r’ determines ‘a’, but in accordance with injectivity rules, f a ∼ f b implies a ∼ b, there - in the definition of Foo – should not be ‘f a’ that returns the same as ‘f b’. Accordingly, ‘f a’ only should be equal ‘f b’ if ‘f b’ is ‘f a’. Concisely, while defining a type family, one has to pay attention that there should be no definitions that return same types. As for the Foo, it has to be changed to the following:

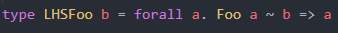

Before we proceed, we must ensure that GHC now can infer ‘a’ of ‘Foo a’ from result ‘r’. To do it we have to define the following type:

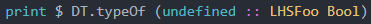

Providing right-hand side type, the type function LHSFoo mentioned above should return us a left-hand side of Foo type family. Let us check it by the following:

The code above returns ‘Char’; that is correct. That is, by the equation Foo a ~ b, then by Foo a ~ Bool, then by Foo Char ~ Bool, and then by Bool ~ Bool GHC infers that ‘a’ from the equation is Char.

Returning to our function fncA, GHC would do the same, given that first parameter is of Bool type: Foo a = Bool, then Foo Char = Bool, so now, it is evident for GHC that ‘a’ is of type Char, and it is all GHC wanted to know.

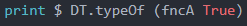

So, the following:

would return Bool, but it does not matter, because what GHC wanted is only to infer ‘a’ from ‘Foo a’.

Second case

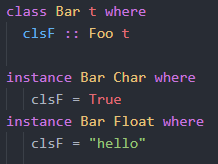

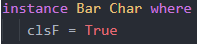

Let us add to the source the following:

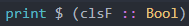

And also, let us add the new print line:

So, here we have two realizations of the function clsF. In the print line, we ask GHC to find the realization that fist the following: clsF :: Foo t = Bool. Having type family Foo being injective, GHC can tell one realization of the clsF from another. That is, only Foo Char = Bool fits the equation, then GHC can say that ‘t’ in the class definition should be Char, and then GHC can find realization of it:

If it were not for injective type families, there could be any other definition of Foo type family that could return the same Bool. Consequently, in that case, GHC could not decide which definition of the Foo type family it should pick and would return an error.

As you can see, Type Families is the powerful tool for type-level programming, but there are some circumstances that one should take into account all the time.